Production of aircraft became a huge industry during World War I. While the government sustained the aircraft manufacturers during this time, this support came to a screeching halt when the war ended.

The civilian industry then depended on investors to build its factories and sales to sustain them. In the second half of the 1920s three factors helped the civilian industry greatly.

The first was the gradual disappearance of war surplus aircraft due to crashes and wear and tear. The second was the unprecedented boom in the stock market. The third was the enormous interest in and publicity for aviation brought about by Charles Lindbergh’s transAtlantic flight in 1927. Not only did his flight inspire people, but his subsequent tour of the United States brought him into personal contact with millions of people.

STOCK MARKET INVESTMENT

By 1925 there was an unprecedented boom in the stock market and financial interests were entering the aviation industry. The Air Commerce Act of 1926 provided a stable platform for the industry and flying. Initial offerings of stock from unknown and unproven companies were swallowed up. It was reported in the 1928 edition of the Aircraft Year Book that “money, everywhere, seemed available for aviation ventures.” In the brief 20 months after the Lindbergh flight, investors purchased aviation securities on the New York Stock Exchange reaching a value of $1 billion.

The Aeronautics Branch of the Department of Commerce reported 199 aircraft registered the week ending Dec. 8, 1928. Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft lists 88 aircraft manufacturers in the United States for 1928. The registrations reported for the first week of December 1928 represents products from 53 companies, 39 of which had only one aircraft listed. This report, 10 years after the end of World War I, gives us a chance to see what’s old and what’s new in aviation.

The Aeronautics Branch of the Department of Commerce reported 199 aircraft registered the week ending Dec. 8, 1928. Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft lists 88 aircraft manufacturers in the United States for 1928. The registrations reported for the first week of December 1928 represents products from 53 companies, 39 of which had only one aircraft listed. This report, 10 years after the end of World War I, gives us a chance to see what’s old and what’s new in aviation.

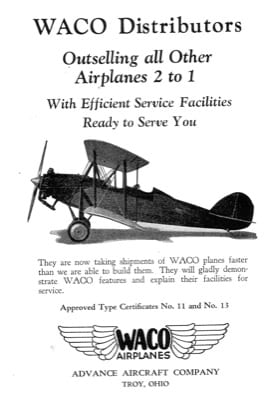

The companies responsible for the largest number of registrations were Curtiss, Waco and Travel Air, which accounted for 28% of the listings. Waco and Travel Air accounted for the majority of those aircraft — a whopping 21%.

The Curtiss entries bring up the issue of war surplus aircraft. All but three of the Curtiss machines — a Robin, an Oriole and a Fledgling —were World War I Jennies. Other war surplus aircraft included Standard J-1 and Thomas Morse Scouts. Ten years after the end of the war, some foreign aircraft were being imported, including Avro Avians and Klemm light planes.

The registration information for the first week of December 1928 was published in the Dec. 13, 1928, issue. The listings were in two sections: Licensed Aircraft and Identified Aircraft.

Licensed aircraft were aircraft inspected by the government and approved to carry persons or property for hire between two or more states and to or from foreign countries. Most of these aircraft held manufacturers type certificates. Leading the registration in this category was Waco with 21 aircraft (22% of market); Travel Air, 8 (8%); Alexander, 7 (7%); Fairchild 7 (7%); and Moncoupe 7 (7%).

Identified aircraft amounted to a register of all other aircraft. Leading the registration in this category was Curtiss, 15 (14%); Waco 8 (9%); Standard, 6 (7%); and American, 5 (4%).

POWERPLANTS

Not only did war surplus airframes have their influence on the market, but war surplus engines did as well. The most used were Curtiss OX5s, but also being used were Hispano-Suizas and LeRhones. The OX5s were not only in war surplus aircraft. Besides residing in the surplus Jennies, they powered 50% of all new aircraft registered in the sample.

The previous year, 1927, saw the introduction of new large radial engines in the 200-400 horsepower range, such as the Wright J5s, Whirlwinds and Pratt & Whitney Wasps. In this report, they were installed on 30 of the aircraft. Their use would continue to increase as the use of war surplus engines had about run its course with the Parks P-1 of 1929 being the last type-certificated aircraft offered with the engine. This was also an era of new small radials, such as LeBlond, Kinner and Scarab. Six aircraft used these engines.

WHO/WHERE

The majority of the aircraft listed were registered to individuals, however about 11 types of aircraft were registered to airlines, including Ford Tri-Motors, Waco 10s, and a Ryan Brougham. American business had become enthusiasts for the use of aircraft and 139 aircraft were registered to companies, including two oil companies. The remainder of the aircraft, 49%, were listed as belonging to private owners.

The registered aircraft were in locations from coast-to-coast. The two states with the largest number of aircraft were New York and California, which accounted for 30% of the new aircraft. Another 30% went to the Midwest, with Illinois getting the most.

INTO THE FUTURE

In 1928 with the growth of air mail, airlines, business and private use of aircraft, and new aircraft designs, civil aircraft sales exceeded military sales for the first time. However, the stock market crash of 1929 and the subsequent depression put a damper on enthusiasm and investment for the young aviation industry.

The $1 billion value of aviation stocks in 1929 was contrasted with $90 million gross sales in the industry. After a four-year ride, returns for investors was reputed to be five cents on the dollar.

There were great problems, but they did not extinguish interest in flying. Aviation was still a young and vital industry with the capacity to draw from its own resources and all the potential witnessed by the public. By 1932 Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft listed 85 major aircraft producers in the United States.

Is it interesting to see how far aviation has come since the first famous flights of Lindbergh and others. Many small airports were first developed for the military for combat training and then after the wars, they were given back to the city. Lindbergh has created great history and it obviously showed in the stock market. My personal interest shows my passion for aviation. I work at Echelon Jets, http://echelonjets.com/ a private charter company and we are all very passionate about finding articles like this. thank you for the share, we have also passed this along to our team.

The dream of flying never dies out. It’s amazing that the aviation securities bought after Lindbergh’s flight totaled $1 BILLION… at the end of the 1920s! Impressive. I imagine Amelia Earhart’s popularity must have helped as well.