Among the many things taken for granted today is long-distance travel by jet airliners. So common is long-distance air travel that there have even been around-the-world races for general aviation aircraft. One forgets that regularly scheduled intercontinental commercial air travel only came into being after World War II.

The roots of long-distance flight lie in the five years after the First World War. In the early post-war period, aviation spread its wings in ever greater long-distance flights, culminating in the first round-the-world flight in 1924.

OVER OCEANS AND CONTINENTS

The post-war period saw great advances made in long-distance aviation, with many pilots and flights making front page news. Aircraft builders, engine makers, oil companies, and others were all contributing to an effort to improve their products and bring glory to their countries. Record setting flights were a means to do both.

The first year after the Great War, 1919, saw an amazing number of long distance flights, the success of which would spur the idea of an around the world ?ight. These included Atlantic crossings and a flight from England to Australia.

The United States Navy mounted a huge effort to be the first across the Atlantic. This effort included four Curtiss-Navy ?ying boats and no less than 53 destroyers strung out at 50-mile intervals along the proposed route between Newfoundland, the Azores and Lisbon. Still, the Atlantic nearly beat the ?ying boats.

One of the flying boats was a non-starter, and two came down at sea. One sank, the other limped into port in the Azores. The last ?ying boat, the NC-4 under the command of Lt. Cmdr. Albert Read, completed the trip and made history. The crew continued from Lisbon to Portsmouth, England, arriving on May 27, 1919, having covered more than 4,000 miles in nearly 60 hours.

ATLANTIC NON-STOP

June 1919 saw the first non-stop ?ight across the Atlantic by John Alcock and Arthur Brown in a Vickers Vimy. The Vimy was built in England during the First World War as a large bomber. Though a large twin engine biplane, the Vimy had about half the weight of the Curtiss NC-4.

The aircraft was shipped from England in May 1919 to Newfoundland, where it would depart for the Atlantic crossing. Departing Canada on June 14, the Vimy headed east arriving in Ireland 16 hours and 1,860 miles later after a terrible night over the North Atlantic. The English were ecstatic about the ?ight. The British journal FLIGHT said that it was the “first real Atlantic flight.” It was indeed an epic ?ight, one that would not be matched until eight years later by Lindbergh.

CONNECTING AN EMPIRE

The Vickers Vimy turned out to be a very good long-distance machine, not only crossing the Atlantic non-stop but ?ying from England to Australia. The second great flight for the Vimy took place near the end of 1919 when the Smith Brothers, Ross and Keith, ?ew from England to Australia. They covered the 11,130 miles in about 136 hours, arriving in Darwin on Dec. 10.

SOUTH ATLANTIC

The South Atlantic was first captured by air in 1922. On March 30, Captains Gago Couthinho and Sacadura Cabral of the Portuguese Navy took off from Lisbon in a Fairey IIID ?oatplane and ?ew to the Cape Verdi Islands. After a stop for bad weather, they set off for the true ocean crossing. They failed to make it to their destination in Brazil, but made a forced landing at Saint Paul’s Rock in the South Atlantic, seriously damaging the aircraft. A second floatplane was shipped and they were able to continue their flight.

This machine was in turn damaged on an island off the coast of Brazil. They eventually arrived in Brazil on June 16 in a third seaplane. Now both the North Atlantic and South Atlantic had been crossed by heavier-than-air aircraft

U.S. ARMY RECORD FLIGHTS

Since 1919, the U.S. Army Air Service had been regularly establishing endurance, distance, altitude and speed records in airplanes to promote favorable publicity and public support for the funding of the service.

In 1919, Lt. Colonel Hartz and Lt. Harmon made a complete circuit of the United States, a distance of 9,823 miles. On July 25, 1920, a flight of four Army DH-4s under the command of Capt. St. Clair Streett, departed New York City for a ?ight to Nome, Alaska, arriving 40 days, 4,500 miles and 50 ?ying hours later. Leaving Nome on the last day of August, the men arrived back at Mitchel Field in New York on Oct. 20. The Air Service’s public relations staff compared this ?ight with the Navy’s NC-4 crossing over the Atlantic.

In September 1922, Lt. James Doolittle, a promising young flier, made the first coast-to-coast ?ight in a single day. He ?ew his DH-4 from Florida to California in 22 hours and 35 minutes, including an 85-minute stop at Kelley Field in Texas.

This was followed in May 1923 by Lieutenants Oakley, Kelley and John Macready, flying an Army Fokker T-2 from New York to San Diego on the first non-stop coast-to-coast ?ight across North America. This ?ight was called “The Greatest Record of All,” one for which the pilots received the Distinguished Flying Cross. An editorial in the May 14, 1923, issue of AVIATION declared the ?ight was “a striking demonstration of the practical uses of the airplane for long-distance travel.”

By now a race to see who would be the first to ?y around the world was developing among aviators of several nations. It would be the U.S. Army that would accomplish the feat during 1924.

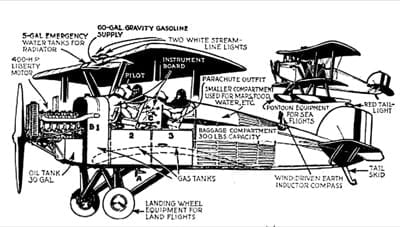

Four Douglas biplanes piloted by U.S. Army fliers under the command of Major F.L. Martin departed Seattle April 6, 1924, to begin the first aerial circumnavigation of the world. The aircraft, known as “Douglas World Cruisers,” were variants of a torpedo plane Douglas built for the Navy and were powered by the famous Liberty engine developed during the war. The aircraft were known as the “Seattle,” “Boston,” “Chicago,” and the “New Orleans.” The flagship, the “Seattle,” crashed in Alaska but the other three would carry on to the Faroe Islands where the “Boston” was lost in a handling accident. The remaining two aircraft would make it to Nova Scotia where they were joined by the prototype World Cruiser now named the “Boston II.” From there the planes flew across the United States, landing at Seattle on Sept. 28, 1924, having accomplished a 27,553 mile flight around the world in 15 days, 11 hours and 7 minutes of actual flying. The first world flight was, by any standard, the greatest aviation achievement of its time. The support requirements were daunting. Worldwide resources of the Army, Navy, Coast Guard, State Department and a host of other agencies and companies were coordinated for the effort. It was perhaps the largest peacetime logistical effort of the era.

With the fame gained by the flight, Douglas adopted “First Around the World” as its company slogan and developed a logo symbolizing aircraft circling the Earth. This symbol continues on today in the Boeing logo after the merger with McDonnell-Douglas.

Dennis Parks is Curator Emeritus of Seattle’s Museum of Flight. He can be reached at [email protected].