During the decade of the Great Depression, the streamlined form stood as an optimistic symbol of progress and efficiency. Streamlining was applied to cars, trains, ships, buildings, and even household appliances. This new idiom replaced the angular, art deco forms of the 1920s.

By the mid-1920s aircraft construction was in need of a new design approach. With the availability of engines with 200 to 350 horsepower, aircraft were flying faster, but not in proportion to the increase in power. With all the higher turbulent flow being experienced at higher speeds due to common design practices of the time, a reduction in drag became important to improved performance.

So in the era between the middle 1920s and middle 1930s, streamlining came into its own in aircraft design.

THEORY

The scientific principles adapted for these modern forms found their roots in the early 19th century dating back to 1804 with the publication of “Essays Upon the Mechanical Principles of Aerial Navigation” by Sir George Cayley in which he described the ideal streamlined body as applied to balloons. He wrote, “I conceived the Bag or Balloon to be in a form approaching that of a very oblong spheroid — but varied according to what may be found the true solid of least resistance in Air.”

In 1809, Cayley reported on his studies of streamlining as found in nature. In one study he measured the girth of a trout at regular intervals and converted these figures to diameters.

From these figures he whittled a wooden spindle symmetrical about its axis. He split the spindle lengthwise and wrote that each half would produce an ideal hull for a boat.

In 1907, F.W. Lanchester set down the basic facts of the drag of an airplane in his book “Aerodynamics.” He said the drag of a perfectly streamlined airplane should amount to no more than that caused by the friction of the air over its surface plus that which was needed to sustain it in the air.

This was counter to the opinions based on Samuel Langley’s belief that skin friction was negligible. Lanchester’s arguments were skeptically received but were supported by Ludwig Prandtl of Germany. Prandtl had presented his first paper on lift and drag in 1904. Both he and Lanchester pointed out that the flow of air close to a body would be either turbulent or smooth (laminar) and that the drag would be far less if laminar flow was sustained. They set the scientific foundations for drag reduction and streamlining.

Though the basic theoretical work contributing to the knowledge of drag and its reduction were set by 1904, it would be another quarter century before serious attempts were made to use this theory in aircraft design.

PRACTICAL APPLICATIONS

1920 — The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) in its annual report expressed its enthusiasm for cantilever monoplanes: “The program of aerodynamical research is to be carried out with a view to the successful development of an airplane incorporating an internally braced wing structure, in order to eliminate practically all the structural resistance, a factor which greatly handicaps the performance of the present ype of airplane. “This research will supply data very much needed in the design of these new types of machines, which, because of their structural permanency, their high load-carrying capacity and their high maximum speed, will undoubtedly be the airplanes of the future.”

Except for German glider designs and racing aircraft, especially the Schneider Trophy aircraft, not much progress was made in applying the principles of streamlining in the early 1920s.

1927 — Lockheed demonstrated the value of streamlining for commercial aircraft with the appearance of the Vega. The plywood monoplane, designed by Jack Northrop, had a very smooth full-monocoque fuselage and cantilever wing. Though lacking an enclosed engine and having a fixed landing gear, it was about 35 mph faster than contemporary aircraft.

1928 — H. Townend of the British National Physical Laboratory published the results of experiments studying the effect of mounting a ring around a radial engine. The result was a sharp drop in drag.

1928 — NACA decided that the first use of its new large wind tunnel would be to test engine drag and the design of engine cowls. The results were reported in NACA Reports No. 313 and 314: “Drag and Cooling with Various Forms of Cowling For a Wright Whirlwind Radial Air Cooled Engine.”

Fred Weick (later of Ercoupe fame), who was in charge of the research, showed that drag from the exposed engine cylinders amounted to one-third of the total drag of the entire fuselage and that completely enclosing a radial engine in a cowl would reduce drag more than the Townend ring without causing the engine to overheat.

1928 — NACA Technical Note 299, “The Effect of Fillets Between Wings and Fuselage on the Drag and Efficiency of an Airplane,” described the results of tests made to determine the effect of fillets between wings and fuselage on the drag and propulsive efficiency of a high-wing cabin monoplane. A nearly 2% reduction in drag was reported.

1929 — B. Melville Jones of Cambridge University presented a comparative study of induced drag and theoretical drag. The paper published as “The Streamlined Aeroplane” provided an easily understood and easily visualized estimate of what could be achieved by reducing drag. He reported: “Reduction of drag will enable an aeroplane of a given power loading either to cruise at higher speed or with a lower petrol consumption. This again will result in increased range or paying load, both factors of importance in aeronautical development. We all realize that the way to reduce (total parasite drag) is to attend very carefully to streamlining.”

1929 — Lockheed Vegas fitted with NACA cowls showed a cruising speed increase of 30 mph.

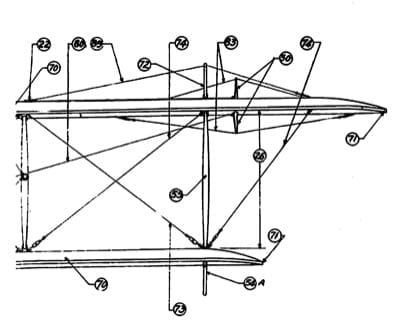

1930 — The appearance of two single-engine, low-wing, stressed-skin monoplanes signaled a new era in aircraft design. These were the Northrop Alpha and the Boeing Monomail. They both were monoplanes with wing fairings where the wing joined the fuselage, improving efficiency and handling. The fairings were developed from the research of Theodore von Karman’s aerodynamics group at Cal Tech.

THE MODERN AIRPLANE

1933 — The newly introduced Douglas DC-1 (Douglas Commercial Model One) bore all the hallmarks of streamlining developments of the time. The twin-engine transport featured a litany of modern techniques: All-metal, stressed-skin construction, cantilever wings, aerodynamic wing-fuselage fillets, retractable landing gear, and cowled radial engines. With the introduction of the production version, the DC-2, the era of streamlining came into full blossom in a widely produced aircraft.

Dennis Parks is Curator Emeritus of Seattle’s Museum of Flight. He can be reached at [email protected].